The development of techonolgy has helped to upload traditional archives to digital platforms that people can use to share information easily and also prevent the risk of physical archive damage. The wide use of social networks in our daily lives also expands the definition of archive and causes our traces or “self-identity“ online to become a new kind of archive.

If you want to study a person, besides going through her/his resume, you can also check her/his Internet accounts. In the academic world, information from social media has already been used as a database. Lev Manovich uses the ten thousands random pictures to construct a database for his project called SELFIECITY (http://selfiecity.net/). Selfie pictures are selected from five cities and were analyzed by face analysis software. In this case, Instagram has participated as an archive.

Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram now are the three main social media platforms people use. In 2008, China banned Facebook, but Chinese created Renren as alternative. Twitter was banned the following year, and the Chinese launched Weibo. Luckily, China has not done anything to Instagram yet. Renren and Weibo are adopted from the originals but have altered to fit Chinese market and Chinese users. I’m not a frequent user of Renren, so I can only talk about Weibo.

The major difference of Weibo compared to Twitter considering their function as an archive is you can trace more information about this user on Weibo.

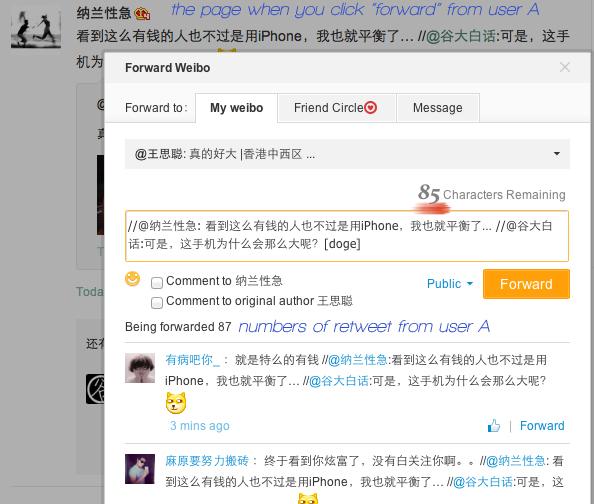

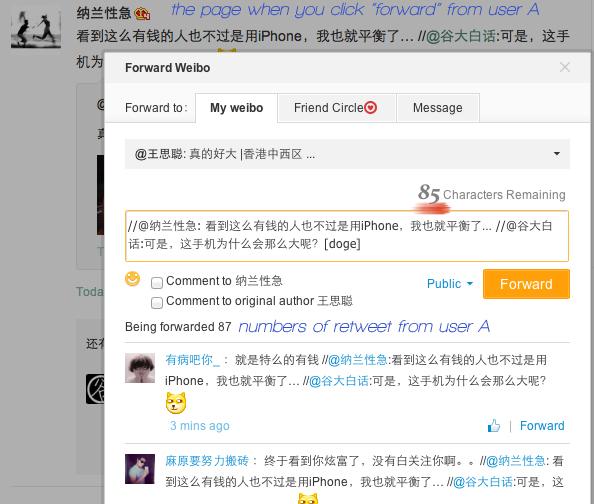

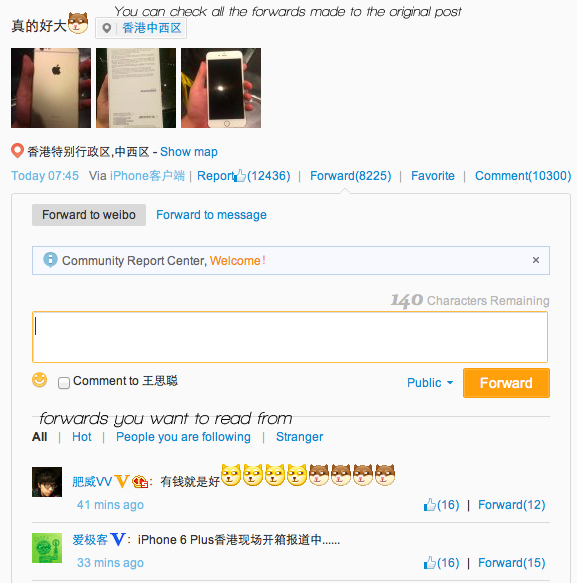

This is what a post will look like:

User A is whom you subscribed to, user B is whom user A subscribed to. You can tell where the post is originally from, and you can also tell how your subscriber found this post. The “forward” is likely the “retweet” in Twitter.

However, you can add comments while you retweet. You can also simply comment under the post by clicking “comment”, which will not be shown on your timeline. You can add @username to remind the author or any people about the tweet.

Weibo shows what kind of platform/which device system you are using to go onto weibo. It is beside the “time” part, after the “via”. It is determined by the weibo phone app.

If more than one people you subscribed retweeted this post, you can also see their “retweet” at the bottom.

When you click “forward” on user A’s retweet, you can see all the retweets made from user A. You can write down your own comment but only 85 characters remain due to pervious comments were being made. You have to share the length. There will be a double slash to separate the two opinions. Weibo considers this as part of your post. So you can delete or edit the previous opinions if you want. One thing about weibo is its privacy. You don’t have to make every tweet public. You can choose to tweet it as visible only to your own friends group. It also applies when you retweet. You can even retweet it via private message. It is like Facebook.

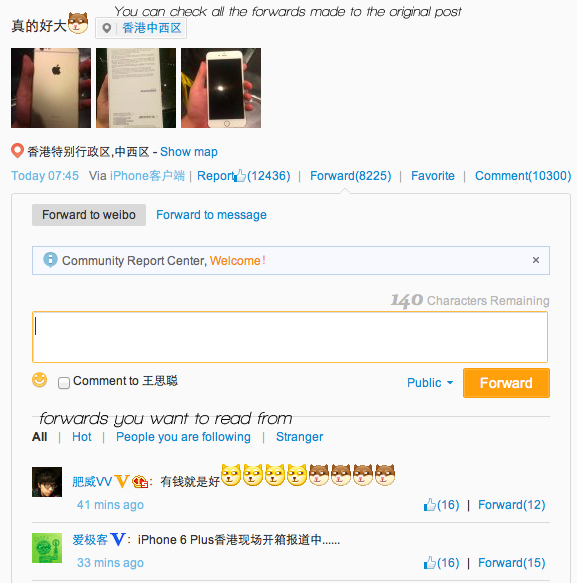

You can go to the original post and check all the forwards (retweet) and comments made directly to the original post. And if you decide to forward directly from the original post, you have 140 characters to comment! Yay!

The “forward” (retweet) and comments allow for more ‘reposted’, engaged, threaded conversation. Twitter users can also share the tweet with her/his followers by retweeting. However, the tweet to be shared can’t be modified.

On weibo, user can do more than that. She or he can add comments or opinions to the retweeted tweet. The opinion is limited to 140 Chinese or 280 western characters.

This is how you “Weibo”.

You can see different potions to insert rich media like images, videos, music, emoticons and polls when you click “more”.

You can see different portions to insert rich media like images, videos, music, emoticons and polls when you click “more”.

Weibo in Chinese means “micro-blogging”, with its hierarchical comments to the original tweet, it seems quite easy to follow and participate in conversation. Weibo has adopted many features from Facebook to fit into the Twitter platform. These features such as the emoticon which people can use to tweet to total online strangers is a representation of the “online-identity”, which can be very different from the one in real life. Comments made when retweeting or those which are read after the previous tweet is also a process of self-consciousness and self-censorship. If you use Weibo as database to study an Internet phenomenon, the numbers of forwards and comments can show you directly how hot and trendy the post is.

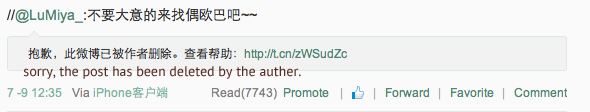

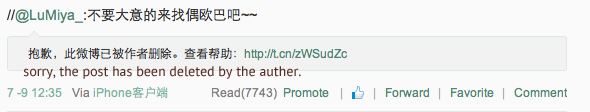

One of the criticisms about Weibo is that it is not simple enough. The conversation may be fun but information can be overwhelming. You cannot directly quote from one comment to reply, which makes it hard to follow (but now Weibo learnt from Twitter again and had the feature of conversation that allows you see the information line). If the original poster deletes her/his post, you can no longer see it, which unlike on Twitter when you RT the tweet, it is on your timeline and no one can take it off.

However, simply being a database or archive, Weibo may have done enough.

Here are some English weibo accounts from celebrities if you want to explore weibo further:

David Beckham, Stephon Marbury, Alicia Keys.

Happy weiboing!

Following up on Martha Joy’s helpful digest of the Twitter workshop, I feel I should make sure everyone has links to some of the amazing platforms for digital interactive education and exploration presented last Friday by Curtis Wong, Principal Researcher at Microsoft Research. I was particularly taken with his early work on the Barnes Foundation collection — a CD Rom that allowed you to explore the galleries on multiple levels before visiting the museum– and his work with Project Tuva— access to annotated lectures of Nobel Prize winning theoretical physicist Richard P. Feynman.

Following up on Martha Joy’s helpful digest of the Twitter workshop, I feel I should make sure everyone has links to some of the amazing platforms for digital interactive education and exploration presented last Friday by Curtis Wong, Principal Researcher at Microsoft Research. I was particularly taken with his early work on the Barnes Foundation collection — a CD Rom that allowed you to explore the galleries on multiple levels before visiting the museum– and his work with Project Tuva— access to annotated lectures of Nobel Prize winning theoretical physicist Richard P. Feynman.